Norwood Press (hardcover)

Norwood Press (hardcover)

Open Road (trade paperback)

Open Road (eBook)

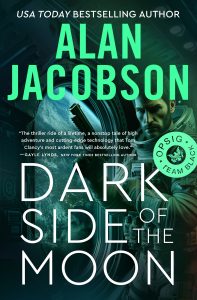

The latest jaw-dropping thriller from USA Today bestselling author Alan Jacobson, featuring the OPSIG Team Black operatives Uzi and DeSantos and the inimitable FBI profiler Karen Vail on a covert mission unlike any you’ve read before…

In 1972, Apollo 17 returned to Earth with 200 pounds of rock—including something more dangerous than they could have imagined. For decades, the military concealed the crew’s discovery—until a NASA employee discloses to foreign powers the existence of a material that would disrupt the global balance of power by providing them with the most powerful weapon of mass destruction yet created.

While FBI profiler Karen Vail and OPSIG Team Black colleague Alexandra Rusakov go in search of the rogue employee, covert operatives Hector DeSantos and Aaron Uziel find themselves strapped into an Orion spacecraft, rocketing alongside astronauts toward the Moon to avert a war. But what can go wrong does, jeopardizing the mission and threatening to trigger the very conflict they were charged with preventing.

New York Times bestselling author Gayle Lynds said Dark Side of the Moon is “the thriller ride of a lifetime…a non-stop tale of high adventure that Tom Clancy’s most ardent fans will absolutely love!”

“Astronauts, space, rockets, fighter planes, action, intrigue—what more could you want? Jacobson kept me turning the pages with his latest riveting OPSIG Team Black adventure. I enjoyed it immensely, and you will too.”

—DALE BROWN, New York Times bestselling author

“Dark Side of the Moon is the thriller ride of a lifetime, a nonstop tale of high adventure and cutting-edge technology that Tom Clancy’s most ardent fans will absolutely love.”

—GAYLE LYNDS, New York Times bestselling author

“A real thriller, with strong characters, intriguing technology, and a story line that kept me turning pages until the very end.”

—BEN BOVA, six-time Hugo Award-winning Sci-Fi novelist

“Jacobson takes international conflict to the new frontier—space, and the dark side of the Moon—in a thrilling, authentic, and thought-provoking way. Like it or not, humanity has entered the next generation of warfare.”

—Lieutenant General John B. Sylvester, US Army (ret.)

“As an expert on lunar geology—and having been a lunar processor and researcher of the Apollo Lunar Samples at NASA—I found Dark Side of the Moon plausible, well-crafted, exciting, and a credible preview of what’s on the horizon.”

—Charles Galindo Jr., planetary scientist for NASA contractor Lockheed Martin (ret.), Northrup, and Tierra Luna Engineering

“Jacobson writes one of his best books to date with this tale of spies, biological weapons, and a moon shot. [Dark Side of the Moon is] a fast-paced and engagingly scientific thriller.”

—Suspense Magazine

“Jacobson’s latest is more akin to the work of Preston and Childs, or even James Rollins. What makes it truly special, though, are the psychological elements he maintains mastery over in crafting a relentlessly paced and riveting effort.”

—Providence Journal

“The hottest thriller of the summer.”

—The Strand Magazine

“Jacobson likes to venture out and write new stories. [Dark Side of the Moon is] extremely relevant. Space is coming to the forefront once again. This believable story shows the importance of America keeping its space superiority [and] highlights how Karen Vail must maneuver through lies, betrayals, and disloyalties to find the culprits.”

—Crimespree Magazine

Dark Side of the Moon | OPSIG Team Black (#4)

Copyright (c) 2018 Alan Jacobson. All Rights Reserved.

APOLLO 17 LANDING SITE

TAURUS-LITTROW VALLEY

MARE SERENITATIS

THE MOON

DECEMBER 13, 1972

“Houston, we’re getting some unusual radiation readings here.”

“Say again? Where are you and what kind of readings are you getting?”

Apollo 17 commander Gene Cernan kept his gaze fixed on the Geiger counter. “We’re on the southeast side of Bear Mountain and—”

“You’re supposed to be on your way back to base,” said flight director Denny Driscoll.

“Uh, this is Jack,” geologist Harrison “Jack” Schmitt said. “This could be an important find. I think we should stretch our safety margin and stay out here a bit longer to—”

“Negative, Seventeen. You two told us ten minutes ago you were drop-dead exhausted from three days of climbing and digging—not to mention hauling Moon rocks for six hours today. You said your hands were tired and chafed raw from wearing those gloves and you were returning to Challenger.”

“This is a once in a lifetime opportunity,” Schmitt said. “Who knows when we’ll get back here?”

In fact, they all knew it was going to be awhile—a long while. President Kennedy’s very public challenge for Americans to land on the Moon before the Soviets had been accomplished—and on time. With budgets strained and the public’s enthusiasm for the space program waning, Apollo 18, 19, and 20 were canceled. The writing was in NASA’s budget—and as good as etched in the basalt of Moon rock: the agency was turning its attention to Skylab and something else they had been discussing: a low Earth orbit space shuttle.

There was a long moment of silence. Cernan figured Driscoll and his mission control specialists were discussing, if not debating, the timing of all they had left to do before liftoff.

Then: “Uh, Seventeen, what readings are you getting?”

Cernan looked to Schmitt. As the only scientist to walk the Moon’s surface, this was his argument to make.

“Exceptionally high CPM on the Geiger. Everything here, so far, is the tan-gray subfloor gabbro that I’ve seen. But the rover’s shadow is making it impossible to see. I think the rock I’m getting the radiation reading from is darker, slicker, graphite-colored.”

“Apollo 14 found uranium and thorium.”

“This is not that.” Schmitt carefully leaned forward, his left hand keeping the heavy pressure suit from tipping him over as he tried to get a better look through his glass helmet visor. “This is…different. And I’m starting to think that maybe the gray, relatively nonvesicular subfloor may be the deeper fraction.”

“Boy,” Cernan said, glancing around beyond them to his left and right, “these rock fields are something else.”

“Dandy,” Driscoll said. “That’s terrific, Seventeen. And I’m glad you’re enjoying the view, Geno. But we’re short on time so tell me about those radiation readings. Can you explain what you’re getting, Jack?”

“I can’t, Houston. I—I um, I don’t know what to make of it.”

“I’m gonna get a picture,” Cernan said as he maneuvered the Hasselblad camera into position and snapped off several exposures. “Got it, I think.”

“Seventeen, Houston. We want you to collect a small, representative rock sample, record its location, and lock it away in the lead-lined box when you get back to the LM,” he said, pronouncing it “lem” and referring to the lunar module. “We’ll analyze it back here.”

“But—”

“You’ve had twenty-two hours of EVAs the past three days,” Driscoll said, using the acronym for extravehicular activities. “But time’s up. You need to park the rover and get your weight balanced for liftoff. Full checklist ahead of you. Go directly back to Challenger and get to it. Houston out.”

Schmitt sighed, the moisture causing a slight fogging of his helmet visor. “A geologist’s dream. And I—”

“You’ve lived the dream, Jack. The only scientist in human history to land on another planetary body. Get your hammer out. Let’s chisel off a piece, take a core sample directly below it, and head back.”

After securing the specimens, they got back in the rover and drove toward the Challenger. Upon arriving, they off-loaded the cases of rocks they had collected, taking care to use the radiation shielded container as directed. They weighed each box and placed them in precise locations to ensure that the ascent stage—which would deliver them into orbit to rendezvous with the command service module—was properly balanced. Every ounce had to be accounted for so they could be certain the engines had enough thrust to lift them off the surface.

“You good with this?” Cernan asked. “I need to go park the rover.”

“Yeah,” Schmitt said. “I’ve got some cleaning to do. This Moon dust is like cat hair—it’s everywhere.”

Cernan drove the LRV, or lunar roving vehicle, several hundred feet from the lunar module and turned in a circle, orienting the front so that it faced the spacecraft. He checked the movie camera mount to be certain it was framing the shot properly. Mission control wanted to film the liftoff, and this distance would give them a good view and enough perspective relative to the surface—as well as a safety margin to prevent the equipment from being incinerated by the rocket engine’s burn.

Cernan climbed out of the rover and stood there a moment, pondering the fact that they had stayed on the Moon longer, and traveled farther, than any other crew had.

He knelt beside the rover and, scraping the stiff right index finger of his glove against the lunar soil, carved the initials TDC, after his daughter. He chuckled, knowing that with the Apollo program now ending, his inscription would remain undisturbed for many decades to come…perhaps for eternity.

He hopped and bounced back to Challenger—the lunar module’s call sign—marveling at what he and Schmitt, and the hundreds of engineers at NASA and its contractors, had accomplished.

Upon reaching Challenger, he grabbed the handles to hoist himself up the ladder. This moment had haunted him for weeks. He had wanted to prepare remarks to read but he never had the time to formalize something. Just as Neil Armstrong’s words of mankind’s first steps on the lunar surface had become famous, the last man making his final boot prints on the Moon might likewise be remembered.

He had jotted down some notes on his sleeve over the past three days, but now, as he stood there, found that he did not need them. Instead, he spoke from the heart.

“As we leave the Moon and Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came, and God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. As I take these last steps from the surface for some time to come, I’d just like to record that America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow. Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17.”

He lifted his left foot from the soil and climbed aboard Challenger.

AFTER ASCENDING THE TEN steps into the lunar module, Cernan was informed that they were over their weight limit by 210 pounds. They had anticipated this would be the case, and like some of the Apollo missions before them, they pulled out a fish scale and began weighing items they no longer needed.

Out the door went a bevy of expensive equipment: lab instruments, pouches of uneaten food, unneeded pairs of extravehicular activity/EVA gloves, two PLSS primary life support system backpacks, a Leica camera, and, last, the handheld scale.

They finished going through their written checklists and reported in to Denny Driscoll in Houston.

“We’re just about on schedule,” Cernan said.

“Roger, Geno. All systems are go.”

“I’m gonna miss this place,” Schmitt said. He sat back in his couch. “Someday, some way, mankind has to find its way back here.”

“Roger that,” Driscoll said. “Someday, some way, I’m sure we will.”

1

NASA

Neutral Buoyancy Lab

underwater training facility

Houston, TEXAS

PRESENT DAY

The two former Navy SEALs broke through the surface of the 40-foot deep, 200- by 100-foot 6 million-gallon pool that NASA used for training astronauts. Although neutral buoyancy diving did not perfectly duplicate the effects of a zero gravity environment, it provided the best way to simulate weightlessness for EVAs, or extravehicular activities, in space or on a planetary surface.

Astronauts who had trained at the Neutral Buoyancy Lab, or NBL, as it was known, and then went on to do EVAs outside the shuttle or International Space Station reported that it was effective in helping them prepare.

Standing on the edge of the expansive pool were FBI director Douglas Knox and secretary of defense Richard McNamara.

As the metal platform rose out of the water, two astronauts wearing modified pressure suits with leg weights strapped to their ankles stood rigidly, back to back.

Harris Welding rotated his head inside the large helmet and waited for the assistant dive operations training officer to help him out of his gear.

Two training support personnel began removing the breathing apparatus from Welding’s partner, Darren Norris, while another unhooked the tank that supplied nitrox.

Once their helmets were detached from the suit, Secretary McNamara stepped forward, remaining behind the yellow and black striped safety line at the pool’s edge. “You’re both doing exceptionally well. We want to personally congratulate you on your progress.”

Welding laughed. “Thank you, sir. But all due respect, the two of you didn’t fly out to Houston just to give us a pat on the back.”

“No,” Director Knox said. “I know it takes forever to get out of those suits, but meet us in the briefing room in forty-five minutes. We’ve got some classified information to share regarding your mis—”

“Daddy! Daddy!”

Three children, two girls and a boy, came running toward Knox and McNamara, with a woman in her late thirties trailing twenty feet behind them.

“Wesley-Ann and Nicki,” their mother shouted. “Stop. Michael, get your little sister!”

Knox stuck out his right arm and corralled the children. “Whoa, it’s dangerous by the edge of the p—”

“Hi Daddy,” the older girl, about seven, said.

A broad grin spread over Welding’s lips. “Hey sweetie. What are you doing here?”

“You’re s’posed to eat dinner with us, remember?”

“Oh. Uh, yeah, sweet pea. But you’re way early.” Welding was still sheathed in his suit and standing rigidly on the platform with a few inches of water from the humongous pool sloshing violently at his boot tops.

The woman reached Knox and gathered up her kids. “Sorry. They get so excited visiting Harris. He’s been training all over the country for a year and a half, so when he’s right in our backyard we try to spend as much time as possible with him.” She held the three children with her left arm and stuck out her right hand. “Tanya Welding.”

“Douglas Knox. You have great kids. They’re adorable.”

“Thank you. Are you—I know your name. But…sorry, I can’t place it.”

“No apologies necessary.” The corners of Knox’s mouth lifted ever so slightly. “I’m with the FBI. I try to stay out of the news as much as possible. It’s not always possible.”

“Sir,” Welding said. “Mind if I take a little time with my family?”

“Absolutely,” Knox said. “Take whatever you need. Just be in the briefing room in forty-five minutes.”

DRESSSED IN NASA T-SHIRTS and cargo pants, Welding and Norris sat down at the oval table. Joining Knox and McNamara were CIA assistant director Denard Ford and Brig. Gen. Klaus Eisenbach from USSTRATCOM, the United States Strategic Command.

“The time has come,” Ford said, “to brief you on certain classified aspects of your mission.” He turned to Eisenbach. “General.”

Eisenbach’s uniform was heavily decorated. He tugged it into place as he rose and walked over to the tabletop podium.

“Are Carson and Stroud getting this briefing too?” Welding asked.

“They are,” Eisenbach said. “But you two are not due back at Vandenberg for a couple of weeks and it couldn’t wait.”

Welding and Norris shared a look, then leaned forward in their seats.

“You’ve spent time studying the Apollo missions,” Knox said, “because they served as the basis for how you’ll be approaching your op.”

Eisenbach picked up the remote control from the table. “The knowledge we gained, the data we collected, the technology we developed, rank among the most important scientific achievements of humankind. But there’s something that came out of Apollo that’s never been publicized or published. Anywhere. Seventeen was the last Apollo, but the first to include a scientist, geologist Jack Schmitt.”

“If I remember right, they brought back hundreds of pounds of lunar rock,” Norris said.

“Yes. Including some odd orange, titanium-laced soil from Shorty Crater that contained the radioactive elements thorium and uranium, which are also found on Earth.” Eisenbach clicked the controller, and the screen behind him lit up with a chemical diagram. “But they also found a new element. Like thorium, it’s radioactive. But we believe it goes far beyond thorium’s capabilities.”

“How so?” Welding asked.

“We only had a few micrograms to work with so we couldn’t be sure of what we were seeing. We couldn’t produce it in the lab so a lot of our analysis required extrapolation and, more recently, computer modeling. I don’t want to get into molecular physics—I’m not an expert so it’d be a short conversation—but this is one of the heaviest elements to be discovered, at the far reaches of the periodic table. Typically such elements are very unstable and highly radioactive. Elements heavier than uranium aren’t usually found in nature. They’re manufactured, so to speak, in linear accelerators in a laboratory. They only exist for thousandths of a second.”

“What’s it called?” Norris said. “This new element.”

Eisenbach cocked his head. “Like everything in science, there are naming conventions and protocols. The name’s unofficial since, to the rest of the scientific world, this element doesn’t exist. But because it could be a great deal more powerful—and dangerous—than anything we’ve discovered on Earth, we’ve named it caesarium after Rome’s emperors for the potential dominance it can provide a country that has it.”

“You mentioned dominance,” Norris said. “Can you be a little more specific?”

“It increases the yield of a nuclear explosion by almost a factor of ten. There are lots of variables with nuclear weapons—the two biggest being how large the warhead is and the height at which it’s detonated. But if you’re looking to cause maximum mayhem and civilian and economic devastation, anything that improves the explosion’s strength and radius by such a magnitude is a major concern.”

“It gives new meaning to the term weapon of mass destruction,” McNamara added.

Eisenbach flicked a speck of dust off his uniform. “It could take out an entire major metropolitan city in the United States with a single nuclear-tipped ballistic missile, the kind Iran and North Korea have been testing. And if they launch multiple warheads and we’re able to neutralize all but one or two—which is likely to be the case—major American cities will cease to exist. And they’ll remain uninhabitable for decades.”

Knox folded his hands on the desk in front of him. “They hit DC? The seat of our government—as well as the strategic planning nerve center of our armed forces—will be gone. Think about that.”

They did.

Welding had a wife and three young children; Norris, ten-year-old twins. Knox knew this factored into their calculus as the seconds of silence passed.

“So what’s our mission?” Welding finally asked.

“We have some HUMINT,” Ford said, referring to human intelligence—spy work. “China is training for a Moon shot. From what we can ascertain—and some of this is unconfirmed—they’re planning to send up a robotic lander and rover to collect rock samples.”

Norris sat forward in his seat. “Are they looking to bring back caesarium?”

“We don’t know. Not yet. We’re working to find out. But we have to assume they are. Even if they’re not, they may find it. We can’t take that chance.”

“So that’s why we’re going up?” Welding said. “I don’t see how—”

“For now,” Knox said, “that’s all you need to know. Once we have more information, we’ll lay down a specific mission plan and explain in more detail what your objectives are.”

Norris held out both hands, palms up. “I can’t believe no one’s ever thought of this being a problem. Isn’t there some sort of agreement that prevents the mining of another planet?”

“They have and there is,” Eisenbach said. “The Outer Space Treaty was adopted in 1967. It basically says that the exploration and use of outer space—including the Moon—is for the benefit of all countries. It’s the province of all mankind. If China’s not planning to share their samples with everyone, their mission would be a clear violation of that treaty. That’s the US position. Of course, if they do bring caesarium back, we wouldn’t want them to share it with anyone. Except us.”

“So it’s a no-win scenario. Once they have it—”

“That’s not all,” Ford said. “The Republic of China ratified the treaty before the United Nations General Assembly’s vote to transfer China’s UN seat to the People’s Republic of China in 1971. The People’s Republic of China described the defunct Republic of China’s treaty ratification as illegal, but the US considers China to be bound by its former government’s obligations. So far, China’s agreed to adhere to the treaty’s requirements.”

“There’s also the Moon Treaty,” Knox said.

“Which no space-faring country ever signed,” Eisenbach said. “Its purpose was to prevent the militarization and resource mining of the Moon without sharing all findings with the international community, through the UN. Like the sea floor treaty.”

“And then there’s the SPACE Act of 2015,” Eisenbach said, “which muddied the water because it gave US citizens the right to commercially explore and exploit space resources, including water and minerals. The only thing excluded was biological life. It specifically states that America is not asserting sovereignty or jurisdiction over any celestial body. But some have argued that the US recognizing ownership of space resources is an act of sovereignty that violates the Outer Space Treaty.”

“So nothing’s really clear,” Ford said. “It also hasn’t been tested—although it sure looks like that’s on the verge of changing.”

“But if China’s getting ready to launch a Moon shot,” Norris said, “and if they’re going there to bring back caesarium, the bell’s been rung. No way to unring it. Regardless of whatever treaties exist.”

“That’s pretty much it in a nutshell,” Knox said. “Which is one reason why you’ve been training for this mission.”

“The other reasons?” Welding asked.

“Reasons two, three, four, and five,” McNamara said with a steely stare, “are…because those are your orders.”

“We’ll give you more as soon as we’re able to.” Ford folded his hands in front of him. “That’s all we’ve got for you, gentlemen. The possibility exists that we’ll be launching sooner rather than later. We just wanted you to be mentally prepared. The rocket was moved to the launch pad several weeks ago and is being prepped. Just in case.”

“Questions?” Knox asked.

“Just one,” Norris said with a shrug. “How will us going to the Moon stop China from launching their mission?”

“That’ll be addressed at the appropriate time,” Eisenbach said. “Anything else?”

A moment later, McNamara rose from his chair. “Dismissed.”

FORD CAME UP BEHIND the men as they entered the suit room to prepare for the afternoon dive.

“Sir,” Norris said. “Something we can help you find?”

“No, no. I just—I think you two are the best of the best and we owe you a better explanation of what’s going on than just the standard need-to-know bullshit.”

“Appreciate that,” Welding said.

“For what it’s worth, I was in favor of telling you more, but there’s considerable…debate about how to move forward. So even if we laid out the approach, things could change. If China forces our hand, I personally don’t think there’s a choice, but for the moment, it’s classified. I know that’s not what you want to hear.”

“I always butted heads with my CO,” Welding said with a chuckle. “I wanted all the info we had so I could be thinking about it, working it through. Just how my brain works. Getting piecemeal info, it’s inefficient. For me, at least. I can be a creative part of the solution, not just a lethal tool who can execute a mission plan.”

Ford laughed. “Then you should’ve stayed in the SEALs and worked your way up to—”

That was the last any of them heard as a powerful explosion rocked the room and the cinder block walls tumbled down on top of them.

2

NASA

JOHNSON SPACE CENTER

MISSION CONTROL

HOUSTON, TEXAS

4:49 AM

The mission control specialist leaned forward and studied his screen. “Hey Sam, check this out.”

Sam blinked his eyes clear and reseated his headset. His oversize coffee mug was empty and he had been caught napping at his station. He glanced at Jamie, who was hunched over his keyboard a few seats to his left in the expansive high-tech monitoring center. Thankfully, Jamie was focused on his station instrumentation. “Whaddya got?”

Jamie made eye contact with Sam. “I’m putting it on the main screen right now.”

An aerial view of what appeared to be a massive rocket filled the wall-size display, an intense magnesium-bright flame trailing beneath it.

“Where’s this coming from?” Jamie asked as he studied the trajectory.

“China, Sichuan province. From what I remember, they’ve got a launch center there, so that makes sense.”

“Switching satellites to get us a better look,” Jamie said. He pushed a button and a three-quarter angle came up alongside the other view.

“Heavy lift vehicle of some kind,” Sam said. “Four liquid boosters mounted to the first stage.” He watched the image another few seconds as the startlingly white flame below the rocket turned orange. “I’d say something on the order of…” He scrawled a stylus across his monitor, finished his calculations, and brought his gaze back up to the screen. “Holy shit.”

“That’s one big mother,” Jamie said.

“Big isn’t the word. If I’m right, that thing is 6 million pounds. About 7 million pounds of thrust. Almost as big as the Saturn V.” Saturn V, the powerful multistage rocket that sent the Apollo astronauts to the Moon, was one of the largest ever to successfully fly.

“Even if you’ve missed the mark by 20 percent…” Jamie’s voice trailed off.

“If I had to guess, it’s bigger than their Long March 3B/E.”

“But China doesn’t have a rocket bigger than the 3B/E.”

Sam swallowed. “Obviously they do.”

“We need to report this.”

“Agreed.”

Jamie got up from his terminal and walked briskly to the back of the large mission control center. He knocked on the glass window of his superior’s office, assistant chief of operations, Zenzō Aoki. Aoki looked up from his desk and waved Jamie in.

He stepped inside, his hands now clammy. Jamie had been assigned to ops only three months ago, but he had worked at NASA for fourteen years. When he requested the transfer, his colleagues told him he was crazy because the work tended to be tedious in between launches. He was about to make them eat their words.

“Sir, we’ve got something you need to see. Main screen.” Jamie cocked his head toward the front of the room.

Aoki craned his neck, then gave up and walked over to the windowed wall behind Jamie. Together they watched the rocket continue its ascent.

“Who?” Aoki said. “Where?”

“Chinese. Sichuan province.”

Aoki crinkled his brow as he processed that. “Mass?”

“Six million pounds.”

Aoki’s left eye twitched.

“It’s bigger than the Long March 3B/E. They were rumored to be developing something called Chang Zheng 5, but I didn’t know they built it, let alone tested it.”

Aoki’s gaze was fixed on the screen. “Yeah.”

“And a vehicle that large would be sitting on the pad for days, if not weeks. How could our satellites have missed something that big?”

“Unless China hid it,” Aoki said under his breath. “Okay, Jamie. I’ll take it from here. Go back to your station. Keep monitoring it until further notice. And get me a trajectory.”

“Yes sir.”

As Jamie put his hand on the doorknob to leave, he turned back and saw Aoki lift the red telephone handset.

“This is Assistant Chief Aoki.” He looked up and locked gazes with Jamie’s reflection off the window. “Get me the Pentagon.”

WARNING:

IF YOU HAVE NOT FINISHED DARK SIDE OF THE MOON, DON’T READ THESE QUESTIONS. They contain SPOILERS!

Following are topics designed to provide a stimulating discussion:

1) What did you enjoy most about Dark Side of the Moon?

2) Was the plot engaging? Did the story interest you?

3) Would you like to have seen Karen Vail accompany the group to the Moon or did you feel it was better to have her handle the leak/mole investigation?

4) Was there one character you found yourself drawn to? If you had the opportunity to spend time with any of the characters, who would it be?

5) If given the opportunity to travel to the Moon, would you do it? Despite years of testing, space flight still contains unknown risks. Would the chance to walk on another planetary-type body outweigh the risks?

6) The budget for exploring–and maintaining our military edge in space–is obviously limited. Would you advocate returning to the Moon, to perhaps build a base and establish a national presence, or do you think we should instead aim for sending Americans to Mars?

7) If you could ask Alan Jacobson one question about Dark Side of the Moon, its characters, or the plot, what would it be?

8) Were you satisfied with the ending? If caesarium really existed, do you think the US should have brought it back to Earth, provided it was only used for study and not for war?

9) Dark Side of the Moon is likely the first book ever to deal with a special forces mission to the Moon. What was the most surprising fact you learned about the future of military-oriented space missions?

10) Alan Jacobson writes fiction but grounds his fictional stories and characters in fact. He spent several months working with experts to make sure what he wrote about spaceflight, moon walks, and so on was accurate based on our existing science. Did this enhance your read of Dark Side of the Moon or could he have just “made it all up”?

11) Did you enjoy Dark Side of the Moon? Please write a review on Amazon or Goodreads and…tell others!